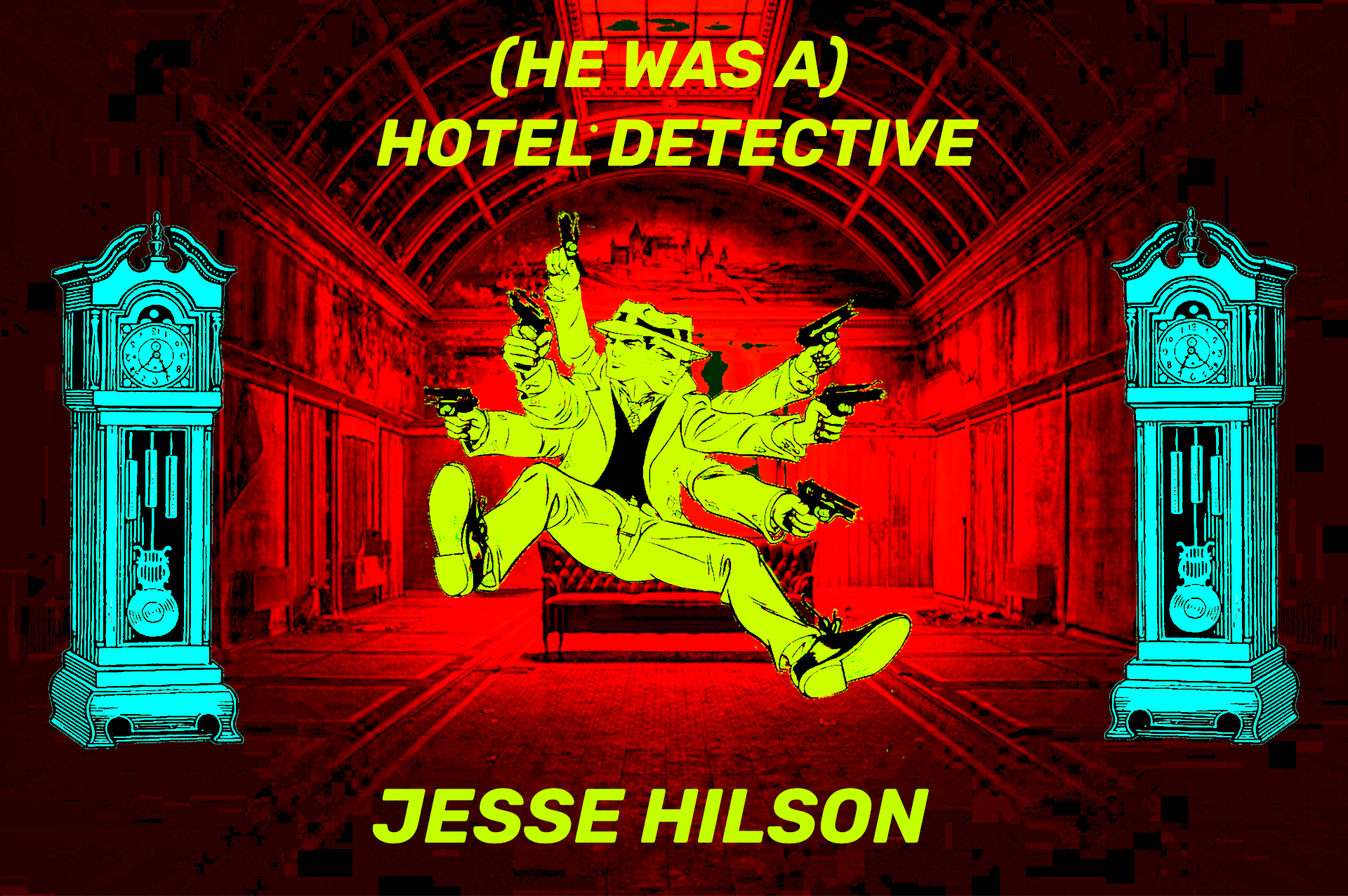

(He Was A) Hotel Detective

I was caught trespassing. Now, in the basement of the Last Estate plantation, I wrack my brain for things to write about to make money for my captors. In exchange for my sorry life, I promised I’d make them money by writing licentious novellas, put them on Amazon Kindle Publishing, then pass all the earnings onto the Last Estate; who, collectively, are a rough master. I ransack my brain for a profitable story idea to feed to Jeff Bezos’ gullet or I’ll be ripped to shreds by Shorty and Lucinda, the gators waiting in the large cistern below the tobacco shed.

I need something lurid, something alight with feverish imagination to slip sideways into the familiar annex of erotic storytelling: between the cracks, that’s what really makes money on Amazon. I pace around my cell, looking through seed catalogs strewn around the floor, casting my mind into its darkest recesses for anything sexual to write about. But anybody can write about sex; it’s the situations, the starting gun you need. The environment, the setting. Something extra, something with that tried-and-true seedy vibe. I pray to the pulp gods, invoking the name of Jim Thompson, the famous alcoholic pulp writer who didn’t hit it bigtime until the afterlife with novels like The Killer Inside Me, The Grifters, and After Dark, My Sweet, among many others. Then, it hits me — to write about my time as a hotel detective patrolling the hallways at the Iroquois Resort Hotel in the late ‘oughts.

Since human behavior in the wee hours has a way of descending into the netherworld, hotels are notorious for their flimsy morality. A hotel detective is an anachronism from Thompson’s era, the ‘40s and ‘50s; a plain clothes guy who monitors the security of a hotel to make sure nobody is breaking any of the rules, assuring there’s no drugs or prostitution. But I was more a glorified security guard or night watchman than a hotel detective proper. Hired by the maintenance department at the Iroquois Resort Hotel, I walked its halls “checking to make sure everything was ok” — mainly listening for freezing water pipes, smelling for smoke in case of fire. The only ash I’d ever detect was the powerful odor of burning marijuana, but nobody’s vices got aired out on my watch.

Like a vampire I worked 11:30 pm to 7:30 am, during the off-season winter months when the Iroquois was all but shut down. To maximize its revenue stream during slow season, the hotel overbooked itself: corporate getaways, golf packages, banquets, ballroom weddings; charging thousands to rent unused portions. But I preferred the hotel completely empty of people, when it came easier to cultivate an air of unruffled authority in the job, something like the security on a casino floor; the guy with the cattle prod who quietly jabs the cheater under the armpit and walks away, sending him tumbling to the floor with the guise of a heart attack before other heavies scoop him up and take him to a back room to fuck him up. The truth is, I wasn’t too imposing. The dining room wait staff and the barbacks cackled at me: What are you gonna do if there’s a real problem?

But I had real problems — being a hotel detective to a locked, vacant, ancient building during the bitter winter offered the peace I needed. Nobody knew this, but just prior to accepting the night watchman position, I had taken a couple weeks to implode at a mental hospital from depression and the relentless stress from the hotel during its busy season. Now, diagnosed with a severe mental illness, I kept it quiet when I showed up for this new patrolling duty. All they told me was that I needed a shave.

Three other hotel detectives I’d rotate with: Carlos was always dressed in a tan trench coat, a baseball cap over his moustache; the merciless staff called him Inspector Gadget. Barry was a short, swarthy, wily, vampiric wise guy in his fifties, the greasy look of an aging gearhead; always smirking, chewing a toothpick, a downstate accent in a leather jacket (years later, he’d be inspiration for the hitman character Gartner in my novel Blood Trip). Finally, there was Bill, a much older guy, an ex-cop in a crew cut. Like me, he wore a suit and tie. Bill had a side job in animal control, the one you call when a rabid animal comes on your property. Forever spinning yarns about shooting animals dead, he brought his firearm collection to the maintenance building. In the basement, he showed me several items from his historic gun collection, including black powder rifles. When an employee whips out guns at work the only thing you can do is just lock eyes with them, nod, act interested, and wait for them to leave. But before I could, we discovered one was loaded —no bullet, just the powder—and he set it off: the loudest sound I’d ever heard.

Wandering eight hours in the graveyard shift around a vast empty building with hundreds of rooms while adjusting to a cocktail of psych meds was like surrendering to a beautiful isolation tank decorated with ferns and old paintings — mind-bending. With subzero temperatures outside, I drove through blizzards to relieve Carlos or Barry on second shift. I read tons of books, wrote lots of poetry. I chased down bats that had penetrated the hotel through occulted cracks in the masonry. When no one was looking I brought an electric typewriter, set it up on the heavy polished wooden table in the elegant Oak Room, and filled the first floor with clacking noise: typing a novel about a smart aleck kid who pretends he’s working class, only to fall in love with a rich girl who dooms him. In Room 300 I’d watch a late-night TV shows with all the lights out, go for a walk, then finish watching the show in the cafeteria in the opposite end of the hotel. The Drinky Crow Show and Xavier: Renegade Angel matched the inner sensation of holding on by the tips of my psychiatric fingers.

I stayed active but with boredom dragging at my mind, I’d compulsively wander. In the dark empty dining room, I’d approach the baby grand piano, positioned up on a riser in the blackness. It centered me as my flashlight navigated the ominous cells of the circular tables, each with its uniform, tentacular lace of black chair legs reaching out to trip me. Setting down the sparkle of my key ring, then propping up the flashlight so that I could see the keys, I’d sit at the piano after and play Trent Reznor’s “A Warm Place,” the only simple melody I knew how to play.

One night I smoked a joint before work and found myself in a random hotel room in the old servant’s quarters watching TV. When a horror movie trailer came on, a terrifying poltergeist face came out of the TV, spooking me so chilly that I stayed away from hotel rooms and sequestered myself in the lobby. People often asked, “Was it like The Shining?” wandering around an empty hotel rumored to be haunted. One of those silly “Ghost Hunter” TV shows came to the Iroquois to film with their night vision cameras and hokey narration. I told them that if there’s ghosts in the Iroquois, they would only make themselves known to somebody who was alone in the building, not a whole a circus of actors, camera crews and sound guy. To prove it to myself I went around the hotel with my own video camera, watching through the lens as I went from ballroom to lobby to cavernous kitchen, unnerved as I watched the video later for details I’d missed.

All the lights in the hotel were kept on, except for the floors that for some maintenance reason were kept in darkness. I patrolled these inky black spaces by flashlight, shining it into all the open doors of the hotel rooms. One night, in the darkened eastern wing, I came around a corner, walking down the hall to complete my round. Like a child descending into a basement then hurrying back up the steps, I imagined something behind me. Instead, in front of me: at the end of the corridor, somebody was there, with a flashlight.

“Who’s there?” I said. No answer.

“I’m gonna call the cops,” I warned. I took a few steps toward the stranger; he stepped towards me. Was it someone from the maintenance dept here really late at night? Why was he shining his flashlight in my face? I got closer; he got closer.

This was the lesson of the haunted hotel: no one was there. I realized where this apparition came from — a mirror just inside the door to a luxury suite had bounced my flashlight back at me. The noises you make as you walk down the hall make you stop when you hear something, and the sound stops when you do, only re-manifested when you’re making noise again. The cascade of periphery-reflections you set in motion in mirrors and glass as you pass, darting out of sight when you whip around to look. The wide veranda facing the frozen lake pops and snaps in the pre-dawn subzero air—an immense sleeping dragon who shifts and ripples irritated wings, only frightening because you’re there to hear it.

From the outside, the century-old hotel is an elaborate cake with half its candles blown out. Looking out a high window, in the ice-haloed moonlight, I can see that my footsteps in the snow of the back lawn end where I must have just remembered something—a book, a key, my life—and turned back.

In Room 213 a TV’s on, yet no one’s been in there for weeks. I creep into the periwinkle dark to turn it off. Ghosts like C-SPAN—or perhaps lament they have no fingers to turn to something racier, something more embodied, like Survivor.

When it’s 3am and your elevator breaks, you can’t radio for help. That’s why I preferred the stairs; where I saw a shade dart away on one of the glass-encased landings. Another view, out another window: in the hotel parking lot, a crispy leaf scurries up a snowdrift and clings to a wrought-iron fence. And, with shadows for swords, the full moon and the orange streetlamp fence all night long, until my shift ends.

I stumble out to my car in the lot, feeling the caffeine swell for the dream-drive home, when something makes me pause. Something ancient clutches my shoulder. I turn around just in time to witness a hot pink smear of winter sunrise above the hotel, appearing behind the western turret.