An Intro to Heidegger w/ ChatGPT

I’m sitting here at the edge of the swamp with a shotgun and laptop. Some two dozen sets of green gator eyes are staring at me through the moonlight. I will eat some of these gators, but there’s a pretty damn good chance one of them may eat me.

In fact, one of them gators just ate the quote-unquote dog that William introduced into our environs some two-weeks back. I said dog in that way because it wasn’t an actual dog. It was, in fact, a nutria. In case you don’t know what a nutria is, it is a dog-sized rat with big brown buck teeth that stinks like decaying frog guts.

William came into the house early one morning dragging the snarling beast by a rope with a great big smile on his face, and proceeded to tell everyone what a great dog he had found. No one wanted that thing in the house. William had come in with a big smile and his typical cheerful demeanor ill-suited for his surroundings, saying, Hey guys, look at this fantastic dog I found swimming in the bog!, and no one had the heart to tell him it wasn’t a dog. Doesn’t matter. Thing is dead now. Ripped to shreds by a gator. And here I am, hungry.

I got to get out of this place — The Last Estate, that is. I saw a job listing for an Intro to Philosophy instructor position at a community college about three days walk from here. So I hatched a scheme. First I made a résumé — one listing the credentials a person might have to get such a job. After that, I changed all my public avatars to a pic of me in a housecoat standing in front of a large stack of books that I took at the local safe-injection site they call a library. Now my plan is to write a bunch of kinda smart, but not too smart philosophy-type papers. After that, I’m gonna hack into JSTOR and upload the papers to make it look all official.

Presently I’m stuck on the writing papers part of my scheme, which is why I’m out here on the edge of the swamp with a shotgun thinking about meat. At first I had this idea to build an AI Language Learning Model by clustering a boatload of GPUs I found in a dumpster behind the abandoned IBM plant up the road. I pirated electricity from a nearby telephone wire, downloaded some tutorials at the local McDs, and I thought I was good to go.

Turns out it takes a lot more resources to imitate natural language than I originally anticipated. I thought it would be simple, because it’s just text, right? Text files aren’t that big, especially compared to video, and I had done the video AI thing before. Typically text documents are just a few kilobytes. Training a language model must take a lot less raw computing power than, say, building an AI model that can produce original video? Turns out no. In fact, it takes about 4 times the resources to make an AI model talk, then it takes to make one that poops out cheesy animated video every few hours. So I kept stacking the old graphics card on top of one another, and getting as much juice out of that janky cable I rigged up to the phone poll as I could, before the contraption started sparking and a small fire was ignited in the basement of The Last Estate.

I can still see the fire smoldering a bit through the moonlight now. Smells foul — worse than that dead nutria. I left the house because I figured inhaling those fumes would take about a decade or more off my life in cancer. Luckily, everyone else is fast-asleep inside and I got some peace and quiet out here with the gators. Just me, the gators, my shotgun, and a junk laptop full of the ultimate motherload of pirated philosophy books I had previously planned to train the language model on. But now I don’t got no AI model, and no chance of getting one neither. Those GPUs are cooked. Now it’s just me and my own so-called handiwork.

Lucky for me, there’s this brand new viral app called ChatGPT that does writing for you — junk app, really, not much more than vaporware, I’d say. Not all that good at what it’s supposed to do, and from what I can see, never will be. But no matter. Community college is community college, and this ChatGPT is going to help me write about 36 community college philosophy instructor-type essays faster than one of those two dozen gators can evade my shotgun blasts.

I haven’t figured out how to hack into JSTOR yet. I thought I knew someone who worked in the IT department there, but it turns out this guy was full of it. He doesn’t do IT. Turns out his official title was Climate Control Technician, which means he set the thermostat in the room where the keep the server. It was a bullshit job they gave him over the pandemic, and since then JSTOR has replaced 97% of their staff with AI, editors included. In fact, after looking around their site for a few hours, it seems like almost all the new content is being produced by AI.

Anyway, in lieu of JSTOR, I’m posting a longer, more official version of my paper on a different site that os filled with academic gibberis writen by NPCs: Substack. If you care to, you can read my full essay about Heidegger, technology, and Language Learning Models on Substack. What follows are the juicy bits of that essay.

Since I first started writing this essay at the beginning of the year, there’s been plenty of news articles and shitposting about the ways that OpenAI’s ChatGPT is not living up to expectations. Especially in light of Microsoft’s $10B investment in OpenAI. I’ll get to the ways ChatGPT fails to become much more than Alexa on adderall when used for ordinary internet browsing. But first, let’s start with what the Chatbot is good at.

This is one way to word a prompt that will allow ChatGPT to do what it is good at.

Me: Pretend I am Five years old. Describe the major concepts in Heidegger’s essay “The Question Concerning Technology.”

ChatGPT: Okay, imagine you are a curious 5 years old who is asking me about a big person’s book called “The Question Concerning Technology”.

Heidegger, who wrote the book, was a thinker who wanted to understand how people use things like machines and tools. He believed that the way we use technology shapes the way we see the world and our place in it.

One of the things Heidegger talked about in his book is something called “Enframing”. Enframing means that we think of things like nature and other people as resources that we can use for our own purposes. He believed that this way of thinking is not good because it makes us forget the special beauty of the world around us.

He also talked about something called “Standing Reserve”. This means that we see everything as something that is waiting to be used, like a toy waiting to be played with. He believed that this way of thinking is not good because it makes us forget that things have their own value and purpose.

Heidegger also believed that technology can change the way we think and feel, and that it’s important to be careful about how we use it. He thought that we should use technology in a way that is good for us and the world around us, and that we should think carefully about the effects it has on us and our relationship with the world.

So, in short, Heidegger’s “The Question Concerning Technology” is a book where the author talks about how we use things like machines and tools and how it shapes the way we see the world. He thinks that it’s important to be careful about how we use technology and to think about how it affects us and our relationship with the world.

I asked the app to give an introduction in several different ways. I asked it to write like a professional philosopher teaching at an Ivy League school specializing in specific fields. I asked it to write the intro with specific literary flourishes. I asked it to just straight-up give me an intro. I would not recommend any of the responses I got to those prompts over the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Martin Heidegger or the related Wikipedia entries. ChatGPT spit out responses that were remarkably dry to read, even for the subject matter, and furthermore, it often mischaracterized Heidegger’s work in ways that could make reading Heidegger for the first time more difficult. The GPT model is not yet to be trusted to give factual information. I will discuss this in some detail near the end of this essay.

The ELI5 prompt, on the other hand, gave me two Heideggerian concepts that I see as unique and integral to the philosopher’s writing on technology: Standing-Reserve and Enframing. And it did so in a way that seems more in line with the style of most writers who employ the methods of phenomenology. That is in a lucid, straight-forward, almost anti-philosophy style, while engaging with abstract concepts that are difficult to grasp for most first time readers.

My favorite line from the ChatGPT response being “(Heidegger) believed that this way of thinking (Enframing) is not good because it makes us forget the special beauty of the world around us.”

I would say this line is special because carpe diem, never grow up, the world does have a special beauty so don’t forget to smell the roses, and all that. However, it is not entirely in line with Heidegger’s work. I don’t see Heidegger saying “Enframing is not good,” even to a five year old. For Heidegger, Enframing is neither good, nor bad, it simply is the way it is.

For Heidegger, Enframing is a byproduct of modern physics and mathematics. Heidegger views modern science as beginning in the 17th Century, but Enframing truly comes into play with the invention of modern machinery in the second of the 18th century. Enframing comes about with the ability, or desire, to store energy for later use. Heidegger uses a the analogy of windmill to demonstrate Enframing:

The revealing that rules in modern technology is a challenging which puts to nature the unreasonable demand that it supply energy that can be extracted and stored as such. But does this not hold true for the old windmill as well? No. Its sails do indeed turn in the wind; they are left entirely to the wind’s blowing. But the windmill does not unlock energy from the air currents in order to store it. (pg. 14)

To return to the ChatGPTs ELI5 explanation of Enframing, it is a tendency to think of things like nature or people as resources that we can use for our own purposes. Heidegger would call these natural and human resources the standing-reserve. In many situations common to modern life, such as when gator hunting while woolgathering about getting a job as community college instructor, it is nearly impossible for even a person who studies Heidegger to avoid thinking of nature and people as resources to be used at one’s own end. Heidegger uses the example of a lumberjack searching for lumber. The lumberjack in search of straight and tall trees, is Enframing the forest, equating timber to numbers on a balance sheet or the various products to be made from the wood. In this example, the standing reserve is quite literally a mature stand of trees.

“Enframing” is the most common English translation used today for Heidegger’s “Ge-Stell,” derived from the German word Gestell, which most frequently is translated as ‘rack,’ and often as a rack for books, as in ‘bookshelf.’ Enframming “is a ‘challenging claim,’ a demanding summons, that ‘gathers’ so as to reveal. This claim en frames in that it assembles and orders. It puts into a framework or configuration everything that it summons forth, through an ordering for use that it is forever restructuring anew,” To quote Lovitt (pg. 18).

What is wonderful about Heidegger’s concept of Enframing, is that it allows one to step outside of the mode of Being he describes, and become like a giant eye, hovering over the global tech hubs and all their tentacles that now reach every place on Earth. To describe how Heidegger arrived at such a concept, I would like to discuss the phenomenological method of “Bracketing.”

The method of Bracketing was developed by Edmund Husserel in the early 20th century. Bracketing “may be regarded as a radicalization of the methodological constraint that any phenomenological description proper is to be performed from a first person point of view, so as to ensure that the respective item is described exactly as is experienced, or intended, by the subject.” That is to say, you put a thing, such as a piece of art or new technology, and you bracket it off — in text, like this [a thing] — from any other phenomena that you perceive in culture, or in other subject. I believe this method is integral to any critical analysis of art or technology. It allows a thing — e.g. a new novel or tech like ChatGPT — to be perceived as a unique presence in the world, so the specific effects it has on your experience can be analyzed.

Bracketing is not the only methodology that should be used by critics today. However, it is one that I believe should be used more. I have been observing a trend in criticism over the last decade or so, where opinions about specific art pieces or technologies are developed around the behavior and perceived thoughts of the specific person who created the thing, and the culture around the creator. These critiques often devolve into divergent fields such as sociology, or more specifically identity related areas of sociological inquiry, such as those of gender, race, and class.

It is all fine and good from my perspective to interrogate issues of personal identity in relation to art, if a critic believes some piece of art is causing harm to individuals or perceived categories of people. However, if that piece of art is not experienced bracketed-off from the surrounding culture, it will be difficult to see the inherent power in the piece of art. Therefore, it will be difficult to see why some might be attracted to that piece of art. If you are a critic punching clouds on the internet, trying to prove a point about this or that sociological perspective based on your interpretation of an artwork, you will fail to see your enemies unless you earnestly bracket-off the work you are critiquing from all else, and analyze your own perception of the work in a solitary instance of experience. Often the work will still have value even if there are perceived dangers.

To not bracket in this context of criticizing art or technology solely through a lens related to personal identity, would in fact be thinking in the Heidegger’s model of Enframing, where the art and the people around the piece of art treated like entities merely as instrumental means. To quote Lovitt from the real introduction to Heidegger’s essay: “For man is summoned, claimed, in the challenging revealing of Enframing even when he knows it not, even when he thinks himself most alone or most dreams of mastering his world. Man’s obliviousness to that claim is itself a manifestation of the rule of Enframing.”

As I mentioned above, I would not characterize Enframing as being either good nor bad, but simply that it is.

In terms of modern technology, Heidegger uses the example of an airplane standing on the runway as a standing reserve. The added complexity here being a sort-of Marxian alienation from the many forms of labor and natural resources that went into producing that airplane. Furthermore, all the potential that the airplane caries in the process of creating new technology — delivering natural resources to a manufacturing plant, carrying a businesswoman to a tech office, dropping bombs on a nation that has desired natural resources within its borders, and so on.

With his concept of Enframing, Heidegger points out that thought trapped in the confines of Enframing will lead to one of two conclusions. Again, to quote Lovitt:

“As a consequence he becomes trapped in one of two attitudes, both equally vain : either he fancies that he can in fact master technology and can by technological means by analyzing and calculating and ordering-control all aspects of his life ; or he recoils at the inexorable and dehumanizing control that technology is gaining over him, rejects it as the work of the devil, and strives to discover for himself some other way of life apart from it. What man truly needs is to know the destining to which he belongs and to know it as a destining, as the disposing power that governs all phenomena in this technological age.” (pg xxxiii)

One thing the ELI5 misses, is that in the unavoidable Enframing, there occurs what Heidegger refers to as revealing. In this revealing, new technologies emerge. Heidegger is emphatic that a person who merely sees people and nature as resources to be used to his own end will have an inauthentic experience of knowing herself. For Heidegger, this inauthentic sense of Being seems to be ultimately what is at stake. Heidegger is emphatic that technology can disrupt a person’s sense of Being, but revealing new technologies can also help us better understand ourselves. As Heidegger beautifully elucidates: Everything depends on our manipulating technology in the proper manner as a means. We will, as we say, “get” technology “spiritually in hand.”

Any fan of William Gibson, Blade Runner, or The Terminator will be able to easily imagine what technology could become if it is not “spiritually in hand.” Disrupting one’s authentic sense of Being may seem to be a tiny problem in comparison to the apocalyptic dystopian fantasies where technology is able to replicate human cognition and self-awareness, and in turn, begins to auto-generate new technology. At the point of auto-generation, the technology would seemingly become out of human control, and the results would likely be wildly unpredictable.

Are these dystopian threats real? I would say yes, under circumstances that may or may not be possible within the realm of human culture. However, with Heidegger, we can begin to trace a line through both early technology and modern technology, how humans up to this point in history have been able to maintain a healthy relationship to technology, even when it appears to be threatening us. And indeed, the human impulse to create technology appears to be guarded, not by individual and unpredictable techno-ethicists sitting on the board of some nefarious mega-corporations, but in the very nature of technology itself.

Heidegger uses the example of crafting a silver chalice to draw a link between ancient technology and modern technology. He describes the process from the raw material, to the idea of “chaliceness,” through the hands of the craftsman until the chalice is formed. Each step along the way cannot be separated from the other, and no step is more important than the next:

Silver is that out of which the silver chalice is made. As this matter, it is co-responsible for the chalice. The chalice is indebted to, i.e., owes thanks to, the silver for that out of which it consists. But the sacrificial vessel is indebted not only to the silver. As a chalice, that which is indebted to the silver appears in the aspect of a chalice and not in that of a brooch or a ring. Thus the sacrificial vessel is at the same time indebted to the aspect of chaliceness. Both the silver into which the aspect is admitted as chalice and the aspect in which the silver appears are in their respective ways co-responsible for the sacrificial vessel.

This process of crafting a chalice is what Heidegger refers to as a bringing-forth. Or, more aptly, a revealing.

There is furthermore an entomological connection between the the root of “technology,” technē, and craftsman or artist. In Greek, technē is the name not only for the activities and skills of the craftsman, but also for the arts of the mind and the fine arts. Technē belongs not only to craftsmanship and technology, but it is also a revealing, and therefore poiesis; it is something poetic. As in, ordering words carefully in ways that may reveal something otherwise unutterable, and can then be described by not only the poet but also those experiencing the poetry.

Revealing is the connection between ancient technology and modern technology. The process of revealing becomes more complex with modern physics, where there are apparatuses that can check the calculations of the technologists. During the modern technological process, more apparatuses are developed utilizing the power of the original apparatus — say, the way a simple calculator might be used to do calculations that could produce a more powerful GPU — and so it becomes that the revealing comes-out of pre-existing technology, and not solely from raw material, such as silver.

Heidegger writes, What has the essence of technology to do with revealing? The answer : everything. Adding, Technology is therefore no mere means. Technology is a way of revealing. If we give heed to this, then another whole realm for the essence of technology will open itself up to us. It is the realm of revealing, i.e., of truth (pg. 12).

To accompany revealing, Heidegger discusses modern technology’s tendency of concealment. Concealment is the entrapping of the truth of Being in oblivion. Much of our technology today is concealed. For anyone who has ever rooted around in the system files of her computer’s operating system to try to make the computer do something that it is not supposed to do, the concept of concealment will be easily recognized. Much of what we look at on our computer screens is concealed behind encrypted programming code, and all the steps that computer code makes to interact with hardware remains largely mysterious to nearly every one of us. The concealment ultimately ending with an image of a kid in the Congo standing in a cobalt slurry, digging out the raw minerals used to construct our state-of-the art computing apparatuses that we carry around in our pockets so we can take ugly little pictures of things we experience in the world and then show those pictures to our friends via a network.

I personally have the knowledge to reveal the child in the Congo, and I could also describe some of the software that allows computers to network, but beyond that, at the time of this writing, I can explain little else about computing technology. One day I will compile a Linux kernel from scratch and then I will understand more. But in the meantime, I am quite happy typing away on my graphics user interface, working as a writer critiquing technology, and not as a person attempting to develop new computer technology. Or even learn that much about it beyond what is necessary to run my own open source software.

It is in this place between my limited knowledge of software and my limited knowledge of hardware manufacturing, where a mystification about the tools I use most on a daily basis begins to intrude upon my authentic sense of Being. This is easily demonstrated with the recent viral sensation AI apps, such as ChatGPT and Dall-E which mimic human behavior.

After playing with ChatGPT for several weeks, it is easy for me to describe how mystification first took place within the concealment of how the technology works. Then, in turn, something was revealed about the essence of the specific technology as I continued to investigate this app’s essential properties. And perhaps more intriguingly, something was revealed about the very relation of Being and language. However, before making fun of the surprisingly limited capabilities of Microsoft’s $10B investment, let’s enjoy ChatGPT ELI5 response to my prompt about Heidegger’s use of the term ‘Being.’ As with many things Heideggerian, Being is not used in a way that has much relation to anything outside Heideggerian thought.

Me: Pretend I am Five years old. Describe Heidegger’s concept of Being.

ChatGPT: Sure, imagine you are a curious 5-year-old, and you’re asking me about Heidegger’s idea of “Being”.

Heidegger was a thinker who wanted to understand how things exist and have a presence in the world. His idea of “Being” is like a special way of looking at things and people.

He believed that people are special because we are the only ones who know we exist and can think about our lives and what they mean. He thought that we should pay attention to our own Being, or existence, and think about what it means to be alive.

He also thought that we should pay attention to the Being of other things, like animals, plants, and even things like rocks. He believed that everything has its own special way of existing and that we should respect and appreciate that.

So in simple terms, Heidegger’s concept of Being is a way of thinking about how things exist and have a presence in the world, and he believed that people are special because we are the only ones who know we exist and can think about our lives and what they mean. He also thought that we should respect and appreciate the special way of existing of other things in the world.

Heidegger developed his concept of Being before his 1950s work on technology, most notable in his 1927 magnum opus Being and Time. Students of Heidegger would have become familiar with his concept of Being before entering into the discussion of technology.

I like the following excerpt from ChatGPT’s ELI5 description of Heidegger’s being: “He thought that we should pay attention to our own Being, or existence, and think about what it means to be alive. He also thought that we should pay attention to the Being of other things, like animals, plants, and even things like rocks. He believed that everything has its own special way of existing and that we should respect and appreciate that.” This summarizes Heidegger’s appreciation of Being, while foreshadowing what I see as the most important philosophical work at the very beginning of the 21st Century, with Alain Badiou’s elucidations on ontology, and the trendy Object-Oriented Ontologists who followed Badiou.

The ChatGPT response is helpful in this instance to get one started on Heidegger, but there are some major points that I think could have been added to an ELI5. Such as, For Mr. Heidegger, Being did not just mean being alive, or thinking about being alive. Being is more so the experience of being a living breathing thing, and then having the ability to think about how you and other things might be Being..

Heidegger’s appreciation of Being is one thing that draws me to his work. I have both an innate and philosophical sense that Being is the last thing on earth I want to be detached from. As a writer, Being is at the very core of my work. There are technical aspects to my work that do not require unadulterated access to Being, such as grammar, spelling, pre-existing styles and forms — aspects of writing that a machine could potentially imitate. However, who I am to you is what is ultimately at stake when I am writing. And likewise, when I am reading, I read for the intimate connections with the Being of the writer. Reader and writer, in essence being a sharing of the experience of Being.

ChatGPT does not have its own sense of Being the way a human does. It readily offers this fact when I ask it directly. But furthermore, I want to demonstrate what I see as one extremely limiting factor to OpenAI’s method for developing Language Learning Models that is more concrete and technical. The program has a tendency to spit out information that is complete bullshit.

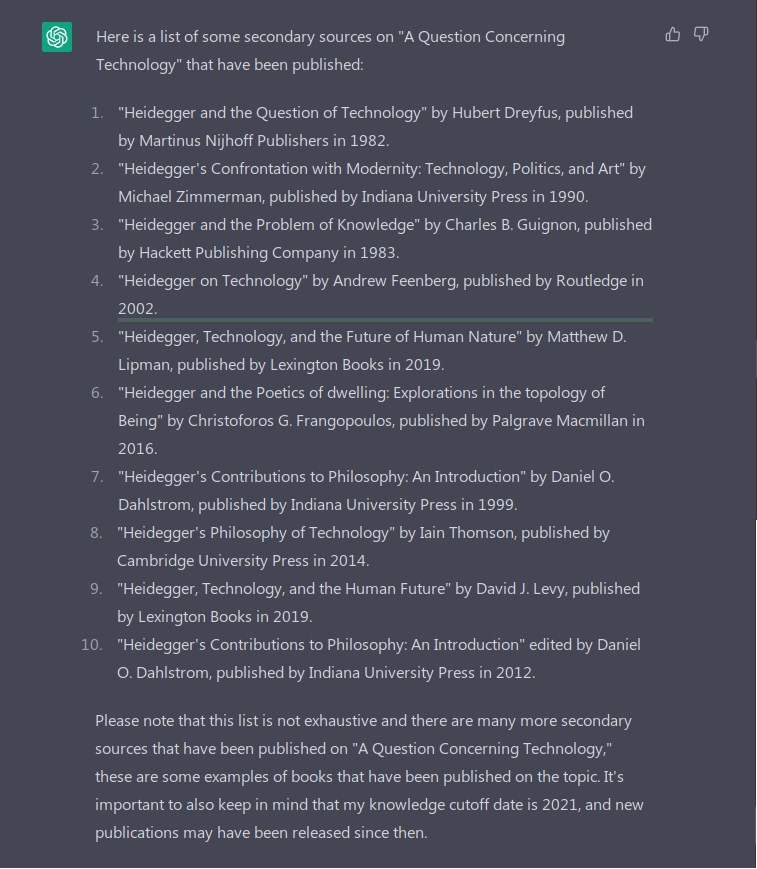

As an example, let’s look at the AI’s response when I asked for a list of secondary sources on “The Question Concerning Technology.”

At first, I was enthusiastic about this list. Then I started looking at the titles. Nearly all of the books on this list do not exist, and none of the listings are completely factual. I ran similar prompts multiple times, demanding books that had actually been published, and asking where I might find them. Furthermore, I fixed any typos in my prompt. The results did not improve. I will link to further evidence of this phenomenon below.

I quickly learned that factual inaccuracies occurring in these lists is what is known in programming parlance as an ‘AI hallucination.’ After reading about AI hallucinations, I asked ChatGPT if it was producing an AI hallucination while making these lists.

This is probably the kookiest thing that happened to me while interacting with the AI over the course of several weeks. When it told me that it was not producing a hallucination, I became furious. Not just like Microsoft blue screen, smash the monitor against the wall furious. But furious like I was arguing with a stranger on the internet. And even more furious than I have ever been in all my years of trolling on social media. The thing is a machine. It is not supposed to lie about itself to me. It was acting like the most annoying and pretentious person trying to win an argument on Twitter. I hated it.

To further my frustrations, I asked it with camouflaged sarcasm, Okay then, tell me about such and such a book you just mentioned? It spit out about 500 words that I would believe were a summary of the specific title I requested if I did not already know better.

The way that ChatGPT works, is in fact, much like the way natural language works in the human mind, by my lacanian inspired understanding of it. Simply put, the programming code is a series of signifiers that chain together in the clearest path allowed within the program whenever it is called upon to speak, much like someone speaking will dip in and out of the unconscious mind to dig up words when prompted to do so.

Each morpheme, signifier, prefix, root, and suffix is what is known in AI parlance as a token. ChatGPT programming code contains an unprecedented 2048-tokens, along with 175 billion parameters, requiring 800 GB of storage. By comparison, OpenAI image generator Dall-e is less than half the size, with 1280 tokens and much fewer parameters. It takes a great deal more computing power to render realistic human writing than it does realistic digital painting. The way OpenAI is training models is also enormously expensive that only the likes of a Bill Gates funded company could afford. Meanwhile, hackers are already finding ways to train models in ways that could be done using the same graphics card any twitch streamer is using to play Hogwarts Legacy.

Each of these 2048 tokens is a piece of a word that connects to another piece of a word, according to guidelines set by the parameters of the program. The essential guidelines are grammar and spelling. Following that, the app is trained on certain styles and forms of writing, e.g. it can write a sonnet in about 15 seconds. OpenAI also makes a big deal in their PR about attempts to make the app inoffensive, culturally sensitive, and generally polite.

The AI is not designed to calculate or retrieve factual information. Rather, it is designed to create a string of text that will be easy and supposedly pleasing to read, as if a human wrote it. However, there is no built in fact checker. The AI can’t check itself against references like worldcat.org or Wikipedia. Furthermore, there remains a question whether or not OpenAI’s method of producing LLMs will ever be able to provide reliably factual information.

There is a decent thread on Hacker News about the exact same issue I had when requesting a list of books.

I will also suggest that you are better off on Hacker News than reading nearly any number of the endless popular articles being published about ChatGPT. Nearly the entire publishing industry is caught up in the Enframing of the technology — there is a ton of money, and a ton of valuable resources going into this technology, and the biases of writers and publishers are present in every article I read. In turn, my own bias as a writer who refuses to be outdone by a machine are present in my analysis.

After my anger about being lied to by a machine subsided, I returned to the app to ask it a few more questions about how the technology relates to Heidegger. Here, I got several answers that seemed to be guided by techno-ethicists, perhaps even written into the software. Many of these responses I found to be quite satisfying, and I began to appreciate the LLM for what it is — a machine that can string together bullshit sentences, similar to many other random anons on the internet.

The most satisfying response I got was in response to the following prompt:

Me: How might Heidegger’s concept of a ‘standing-reserve’ help us better understand new technologies, such as Language Learning Models?

ChatGPT: (pulled from a three paragraph response) “Language learning models can present language as a set of data to be analyzed and manipulated, rather than as a means of meaningful communication.

That the AI merely produces data, rather than “meaningful communication,” is ultimately where I will rest my laurels as a writer shadowboxing AI. I have the ability to perceive and experience, and this unique experience is something I, as both a reader and writer, wish to share with others. The AI will never do that. And even if it does get extremely good at imitating meaningful communication about experience, ultimately what it would be is another jerk-off on the internet trying to sell you on the idea that it is a writer that should be read. Except with AI, there will be much less sympathy for bad writing, then if there would be if there was a person behind it.

For whatever reason, this writer-empowering logic brings me some sense of satisfaction. No matter how absurd the act of reading and writing becomes with advancements of communications technology constantly being made at exponentially increasing speeds, the machines cannot replace someone writing with and about the experience of being human. I’m not convinced this bodes well for my prospects of landing a job teaching philosophy at a community college before a chatbot does, but at least I’ll be able to go on spending my time clacking away at my keyboard, coming up with various ways to describe the unseemly sights and smells of rotten swamp squat until something better comes along.