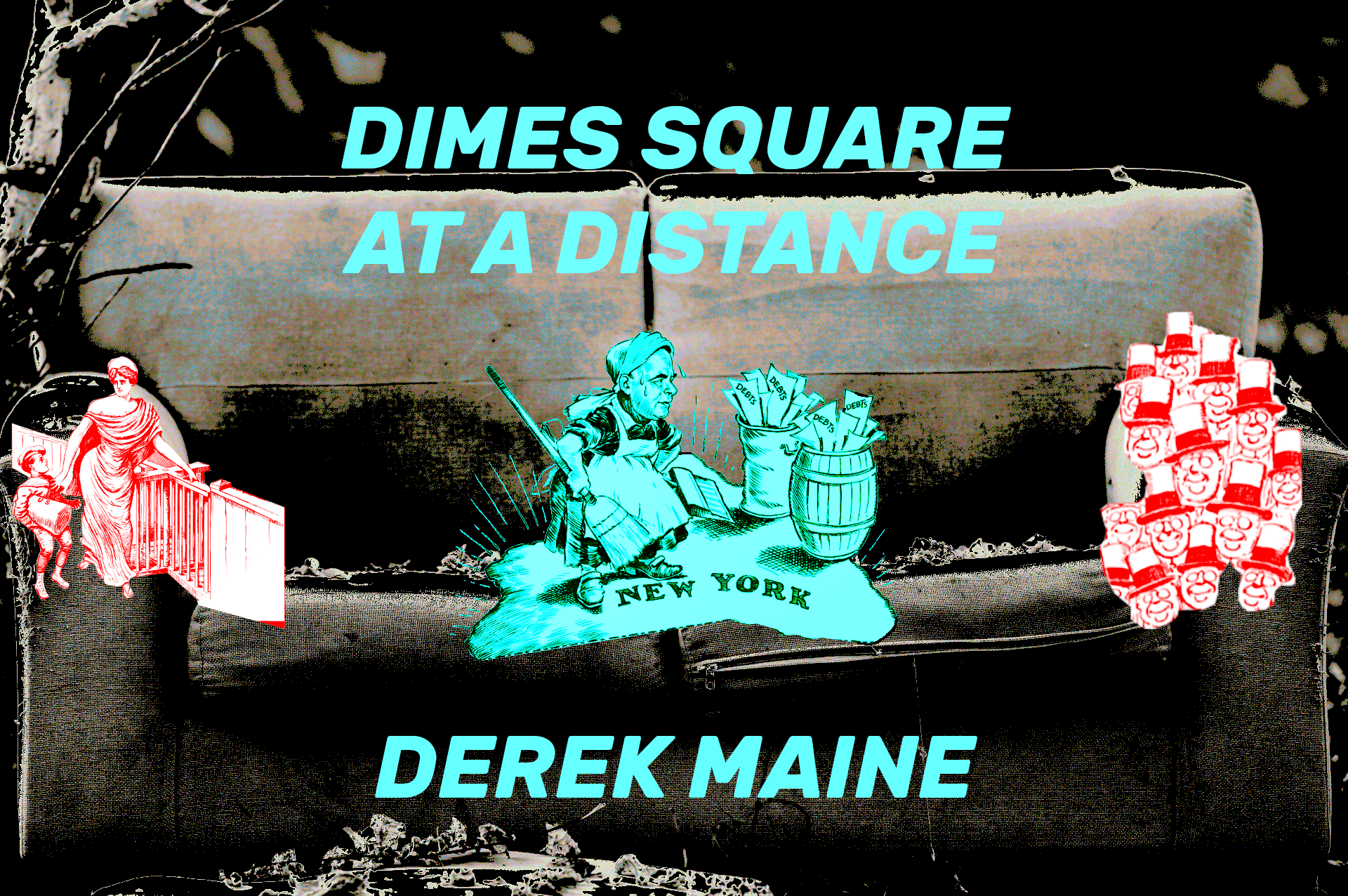

DIMES SQUARE AT A DISTANCE

A Review of Matthew Gasda’s play ‘Dimes Square’

SETTING:

My algorithm blinks + buzzes for weeks with cryptic signs, sigils, and digital monuments, triangulations from a block, maybe two, in the lower east side of Manhattan. Why did it choose me? I am afraid of New York. I live down south, in the flaccid, comforting exurbs, ten minutes to an apartment my aging parents rent, ten minutes to the ballfield, ten minutes to the pool, ten minutes to the Circle K, ten minutes to everything and nothing. Much of my life plays out in one of three rooms, all of them separated by very few footsteps.

I take an unhealthy interest in the lives of others. I begin to take notes and fixate on certain lines buried in cultural commentary:

- “She had to figure out a way to pitch to her boomer editors whatever she was going to write about this corner of the downtown scene, “Dimes Square,” “angelicism,” and so on.” (Mike Crumplar, mcrumps Substack, 05/27/22)

- “But in these days of anti-woke film festivals and blackpilled Substacks, the proper noun ‘Dimes Square’ signifies a bit more than it used to, looming larger in the city’s imagination, having become a concept, a chimera, a state of mind.” (Will Harrison, The Baffler, 05/24/22)

- “You’re supposed to laugh at the backstabbing coke-binging clout chasers not because of how alien they are but because of how familiar they are. You’re one of them.” (Mike Crumplar, mcrumps Substack, 03/01/22)

- “Performed in packed lofts across town – I attended a showing in an apartment belonging to novelist Joshua Cohen, recently awarded a Pulitzer prize for his novel The Netanyahus – the play dramatises the petty rivalries and self-serving ambitions of the scene.” (Nick Burns, The New Statesman, 05/26/22)

To expel these intrusive transmissions, I write a parody of an ending to an imaginary article and post it immediately on twitter – doggedly proud of my abilities to dissect and distill the coverage of a scene and a group of artists I know absolutely nothing about in ten minutes from the comfort of my iPhone.

It quells nothing. The buzzing gets louder.

I decide I want to read the play Dimes Square by Matthew Gasda and actually review the piece of art as it appears on the page. I reach out. I find him responsive, polite, and he agrees to send me the unpublished play to review. The distance between us is immediately evident when, in that first (and still only) conversation between us he tells me I should put the play on myself, in a house down here, and I explain if I did so it would only be for the pleasure of my kids’ friends’ parents.

I. SCAFFOLDING:

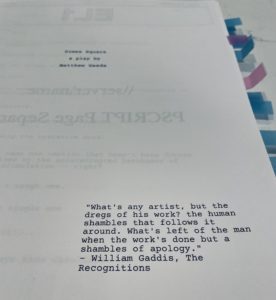

The epigraph, from William Gaddis’ The Recognitions, sets the stage both in themes and atmosphere.

Thematically, we are going to venture into a world of artists, the dregs of their work, and their human shambles. But The Recognitions quote does more than that too, as it immediately recalls the lengthy, dense yet uproariously funny party scenes, over hundreds and hundreds of pages, satirizing the bohemians, beatniks, and New York socialites of Gaddis’ own era. Textually, as I wanted to experience this work of art, it is an incredibly effective introduction to what unfolds. That Dimes Square is not itself a satire won’t settle itself for another ninety-nine pages.

The setting is an apartment in the eponymous block in the lower east side of Manhattan. “Foucault stacks on the floor…” along with detailed, hyper-specific stage directions on how, when, and how much coke to do serve as the only atmosphere we need to immediately locate ourselves.

The cast of characters is eleven scenesters. Most of them in their twenties or just thirty. One 19-year-old. A 45-year-old and 55-year-old. They are writers, editors, students, musicians, artists, filmmakers, a journalist and a fashionista. The action is simple: they sit on the couch, in various combinations, and smoke cigarettes and do coke and talk shit about the scene and each other and themselves.

II. SCENE:

The coverage of the play, and the scene, at times inseparable, loves to focus on the status and celebrity of certain cast members. A famous novelists’ talented daughter! A well-respected literary critic! Performed in the living room of a Pulitzer-Prize winning Novelist! It adds something to the allure of seeing it, for certain, but it also hints at something deeper: the desire of the critical playgoer to inhabit the lives of the cast and characters — both real and personae (intertwined in service of both the play and the century we find ourselves in) — and when the critic does not get what they want (and how could they?) they pan it or mock it or focus entirely on its (light, minor) transgressions or imagined politics.

The social dynamics will be familiar to any artist navigating a world mediated by access. At one point early on, Iris, the “MFA Poet,” asks the writer, Stefan, “who even let him into the scene? Was it you?”

We want to be in that living room with those people having those conversations and doing those drugs. We watch the scene unfold. We watch the uncomfortably familiar social climbing inherent in any scene, and we watch them perform a version of their lives we imagine. The parasocial relationship is front and center in the play and our everyday lives.

This might be a world where a passing mention in a Substack or an inside joke in a podcast denotes clout and acceptance. But the characters here didn’t make the world. They just have the unfortunate luck of living in it and Matthew Gasda is reporting live from it. The characters seem like they are having fun and, if I had to guess, this is a big part of why the coverage of the play and the scene is itself so joyless, either due to our jealously, FOMO, or just basic puritanical guilt keeping us from imbibing in the same unabashed revelry when we are constantly told how awful everything is.

The characters in Dimes Square are not immune to the awfulness. They live in the same world as their audience. The hedonistic thirst for drugs, sex, art, belonging, and recognition is a stubborn refusal to wallow in it and resign themselves to trauma (their own or of the collective) as identity.

Like anyone else, they are constantly obsessing over their petty human dramas. Midway through the play, Bora, the Cinematographer, tells Stefan, “You surround yourself with people you secretly hold in contempt.” Scenes, and in particular countercultures, are brilliant breeding grounds for resentments and Gasda is at his best as a writer when he digs all the way into the neurosis and insecurities of his creations.

There is also no shying away from the particular indignities of our hybrid digital/physical lives. Who follows who, who said what on twitter, who messaged who; all of it flows as easily as who saw who where, who’s fucking who, or who has the drugs tonight. The line between these two spaces, digital and physical, is as intentionally paper thin as the line between cast and character. This is a play, at least on the page, so drenched in naturalism that it can feel more like we are peeping into a Dimes Square apartment than experiencing a theatrical production. This effect is dizzying, intoxicating. During the pandemic social lives ground to a halt. The parties shut down, the bars and clubs closed, and we became floating heads with filters, avatars for a life we wish we had. We became desperate, lusty voyeurs. Matthew Gasda expertly feeds our desires by bringing a scene to a living room and selling tickets to ogle, gawk, and leer.

The characters even worry about their own balance:

KLAY: Fuck, I’m way too online aren’t I?

IRIS: You’re like, Tweeting as we speak, so.

Ashley, the youngest at 19, a college student, is able, perhaps through the clarity of youth, to sense there is something sinister in the scene she’s found herself in. This leads to one of the more poignant moments of the play when she asks Rosie, an artist, if she should “like really invest time in this world?” After a definitive no, Rosie distills the scene perfectly in one beautiful, universal line, “It’s a bunch of social climbers railing coke at 4am shitting on their so-called friends.” In this way the audience is not let off the hook for their own desire to sit on that couch and rail coke and shit on, and with, these people, for access and even, perhaps, a shot at acclaim. The participants are never unaware of their roles, either on the page or in the streets.

Are they obnoxious & pretentious & petty & miserable? Of course. They’re fucking scene kids. They are also brilliant & funny & sexy & real. There is no dignified way to be a human being.

III. SPECTRUM:

Much of the coverage of the scene is devoted to their politics. Their ideology. Their vibe shift. Whispers, everywhere. Angelicism. Catholicism. Peter Thiel money.1 Transgressive. Anti-Woke. Aristocratic. There is the spectre of a philosophy at the heart of this nascent collection of beautiful freaks and weirdos.

I wanted to study the text. I wanted to experience the art for myself, in my preferred style and investigate like a kid with a Visceral Realist super-secret decoder ring.

There are philosophers scattered throughout the text. The three sentence setting instruction calls for stacks of Foucault “on the floor.” A character talks over another with a Nietzsche name drop. A dig on the “ideology of a professional managerial class.” Rosie admits to being “really into Catholicism lately.” Stefan needles Terry, the filmmaker, about starting a Delueze reading group then a Benjamin reading group, Adorno and Zizek. But all of it is in the service of atmosphere over allegory. These are signifiers for an in-group, like green matcha tea or Ukraine Flags for their Williamsburg brethren. All of the philosophers, theorists, and religious curiosity do is suggest a sincere, serious search for truth, meaning, and intellectual stimulation. They don’t seem willing to accept the status quo but if everything is so awful then why would any sane, loving person accept the status quo?

There is a veiled reference to those infamous Thiel Bux when Terry, discussing the realities of financing a film, says: “There are so many things in my head that want to get out. That’s all I care about. Scrounging for resources is a necessary evil. Dealing with sociopaths is a necessary evil.”

As to an actual philosophy present in the text? Any that does exist is presented as fairly standard young nihilism, an affect more than anything else. There are cracks in this superficial nihilistic candy-coated shell, of course. Fittingly, they come from the youngest, Ashley, presumably the least dead inside as yet: “I just don’t know how much longer I can pretend to be this person who doesn’t feel anything.” It certainly seems more indebted to Less Than Zero than a Céline pamphlet.

Why the obsession over their politics and ideology? We live in a time of ideological purity without any decent, feasible ideologies. Communism and socialism? It’s resource hoarding time as we all collectively hurdle toward less and less usable natural resources and you think we can Robert’s Rules our way to peace, love, and happiness? There is so much more death, destruction, and decay coming our way before we get anywhere resembling there. There will be rubble before there will be revolution and some of us have to live through this part too. In 2022, a political ideology might tell us practically nothing about who someone is and everything about how someone copes. The dusty old rags and liberal institutionalists chasing down the ghost of a young, alt-right Manhattan fear a great reshuffling, as it threatens to throttle their corporate power. The barbarians are the gate & they/them are sipping limoncello in Bushwick, Beverly Hills, and Brussels while the rest of us fags argue about the word ‘retard.’

The political philosophy underlying Gasda’s chattering class of today’s bohemians is, if anything at all, one of desperately wanting some alternative to all the shitty political options and identities available to them. This hits me as a universal urge shared by every young group of interesting, bright, sexy, smart artists and thinkers that ever lived or probably ever will. Towards the end of the play Iris, the twenty-five-year-old MFA poet, complains to Klay, the thirty-year old “Journo dude,” of having no means to meaningfully dissent.

KLAY: Dissenting to what?

IRIS: The way things are.

****

The thread holding the scaffolding, the scene, and the spectrum together is what the play ultimately celebrates and achieves: great art. There is still fun to be had in the creating, witnessing, and talking about great art. There is a tremendous monologue by Dave, the elder, accomplished novelist, three-quarters of the way through the play, where he eviscerates a fellow writer. It is so well-written, blade so well honed, an absolute blast to read and re-read aloud.

Several pages later, Chris, the oldest of the group, and Dave’s editor, lays into a young writer and it speaks to me also as a sturdy dissertation on the difference between what they are performing in this play (& what they also perform in real life, each night, in apartments across the lower east side of Manhattan and in Brussels, Berlin, even somehow Toronto) and the work of art itself. “…you don’t tell your kids about meeting ‘relatively clever’ at a party. No. Hell no. You get hard for shit that will survive over time…”

As the work of art itself, Dimes Square is, on the page, decadent and delicious. I fucking loved it.

From a distance. Dimes Square from a distance, on the page, is an exotic, enticing subject. I viewed Dimes Square from a distance, in the theater of the mind. I see Dimes Square in the distance, filling me with quixotic fantasies (like so much great art). I regard Dimes Square at a distance, unconcerned and blessedly disconnected from the clout wars and social climbers jockeying for a spot on the fire escapes of Chinatown, and am instead touched by the beauty in its vanity, and delight in its narcissistic charms.

- Full Disclosure here: The publisher of my novel, Expat Press, put on a reading during the now-infamous NPC Fest in 2021 where Curtis Yarvin read poetry and The Last Estate has had high-level, executive editor meetings debating a pitch deck to plead for our own Thiel Bux. You can only buy my debut novel, Characters, directly from Expat Press. This footnote is very important, William. Do not remove it. Don’t let Stu swap out the hyperlinks again either.