EXPAT RISING: A THREE-PRONGED REPORT ON A YEAR IN THE LIFE OF THE POPULIST PRESS AS TOLD BY A RELIABLE YET INCREMENTALLY SUBJECTIVE NARRATOR

In our age of Amazon feudalism, the claim of running an indie press is a noble but foolhardy endeavor. Even if you’re one of the few successfully moving units, your passion is ultimately neutralized by the Big A monolith who give pennies on the hard-earned dollar. Indie presses are pressured to sell through Amazon, otherwise they feel they don’t exist. Coyly, they beg for reviews – literally, gold stars for playing the game – because a press will feel they don’t exist enough in the fickle yet ever rising ocean of corporate owned tunnel-vision commerce. A visit inside some indie press offices might reveal further cynicism: surrendering to genre formulas, intimidating authors to remain politically-correct, pressuring larger social media presence, charging writers to submit, clandestine author blacklists — all indications of surrender to the increasingly monopolized marketplace.

It could be brushed off as bad habits adopted by and from the uber-ambitious — “if everyone else is doing it, why shouldn’t I?” But that argument doesn’t really hold when you consider NYC’s Expat Press. The editor in chief is Miami-born Manuel Marrero, author of the challenging, idiosyncratic Not Yet Vol. 1 & 2 (Expat, 2019), in which he uses language the way some cultures traditionally consume the entirety of an animal.

He calls Expat a manifestly populist press, fueled by a spirit of defiance rather than the cloying middle-of-the-road approach. Since 2015, Manuel and his inner circle have been rallying against the de-facto literary paradigm, establishing a free-range stable of un-pandering authors who magnetize a vast uncompromising readership; all while giving the middle-finger to the global company store.

“We’re fighting over every margin at Expat, which is why we’re such an existential threat,” he says. “The authors I work with are on the same page, they don’t give a fuck about Amazon. We don’t need them.”

A fiercely transgressive imprint, the energy of Expat surges where punk ethos and artistic sophistication converge. Visually, an Expat book might remind one of an expensive art-reference digest, yet it contains enough inflammable material to burn a whole gallery down. The cover aesthetics, executed by NYC artist Arturo Herman Medrano, are a thread weaving through the catalog.

Staying true to his populist vision, Marrero approached the press’s pandemic survival as a chance to disseminate information for Expat’s cultural moment — he made PDF’s of every release free to download, which in turn moved the hard copies, which in turn assured the press’s most successful year to date in spite of the industry’s scrambling frequencies.

“Expat felt like Grove Press to me when I first started buying the books,” says Anthony Dragonetti, author of Confidence Man (Expat, 2020). Dragonetti went from Expat fan, to Expat author, and is now part of its editorial masthead.

“I hate words like ‘transgressive’ or ‘dangerous’ — we’re talking about books here, calm down. But what really drew me in was the philosophy of publishing what a bigger, more mainstream press wouldn’t touch with a ten-foot pole. Expat has authors from all walks of life. What unifies them is they keep it real. Sometimes that vision is ugly. Sometimes it’s inscrutable. It’s often so honest that it hurts. That rawness is palpable with everything Expat releases. It’s inspired a mad devotion, which is what any small press needs to survive.”

Another way the press survived the pandemic — they began publishing new pieces of writing daily on their site from mostly unknown authors, proving in real time how wide their influence was spreading. Ever contrarian, Marrero considers Expat less of a publishing house and more of “a playground, a stateless ghetto.”

“We want to attract people cryptically, because that’s how you get the most intellectually and otherwise diverse people, even if they don’t all get along. The je ne sais quoi is like an inkblot beacon bringing people to us. It curates itself,” he says.

And indeed, the surprises keep coming. Nothing could have prepared the public for the release of Fucked Up, the 858-page debut tome by nihilistic queer author Damien Ark last November. It’s not so much a novel as it is pure immersive trauma — a book that isn’t read as much as it’s experienced, for better or worse. Since Marrero is a master of language and style, the press releases he writes are a large part of Expat’s manipulative seduction:

“Fucked Up is a relentless onslaught of brutality to stagger the fainthearted, an incomparable monolith, a testament to what is printable, a spectacular orgy of the gruesome and profane, of violence and depravity raw, uncut and unadulterated, eerily prophetic, bearing an uncanny resemblance to modern times.”

It might read as hyperbolic, but I read Fucked Up and it altered me — to the point where I must be mindful of the delicate sensibilities of those to whom I might recommend it.

But this isn’t to frame Expat as some kind of edgelord press. Some of their books find their strength in their focused subtlety, like James Nulick’s The Moon Down to Earth. An intimate eight-character close-up of a down-trodden American desert town, Moon orbits around an affair between a black teenage pizza delivery boy and an older obese, unemployed white woman. It’s a story so delicate, yet lodges itself firmly into your psyche, every word meticulous and haunting. Because Nulick may be the eldest, most experienced author on Expat (he studied under William T. Vollmann in the nineties) he acknowledges the press’s vitality:

“Manuel has a keen eye for finding young new talent,” says Nulick. “Expat’s maximalist books house a barely containable exuberance that pretty much puts the final nail in the desiccated sad boy husk that is alt-lit, thank God.”

Another successful maximalist experiment is Nikolai Andreyevich by Ted Prokash, a rowdy Midwest author of deceptively wide range. Prokash reinvented himself again here by re-creating the style and themes of classic Russian literature in order to prove “that all people, even when separated by hundreds of years of history, or thousands of miles of geography, behave about the same.”

The most anticipated release of 2020/21 would be Expat 4, a thirty-author statement of intent through contemporary situationist prose. It would be a disservice to call it an “anthology,” as its presentation creates an impression of a sustained sacred, confessional, sometimes mad text. At one point during its confrontational online promo campaign, Expat claimed its theme was “fear.” Surprisingly, nowhere in the book is that theme mentioned, besides the unraveling of the writer’s works — the theme’s subsequent removal creates a conspiratorial energy as you read it, an interactive paranoia suggesting the authors know something you don’t. But the further you read, the more you’re indoctrinated into its very “now” madness. It’s an inclusive move for Expat, aligning unknown writers with much more established ones. Yet, there are no author bios — no cluttering end credits of chest-beating resumes. Only clean, classy confidence of the work contained — another notch of an Expat author’s self-reliance that adds to the mystery, the authenticity, of their canon.

If authenticity is Expat’s goal, the wildfire press may have met its incendiary match in Los Angeles outsider author Elizabeth V. Aldrich, known to friends as Eris. The German/English/Columbian 28-year-old has lived a whirlwind. Raised in a Japanese doomsday cult in the San Fernando Valley before moving to the Bay Area to become a peepshow girl at The Lusty Lady, she’s now back in L.A. barricading herself in the sanctuary of her bedroom. Her debut novel Ruthless Little Things is an Expat bestseller, only Eris wasn’t present for its release last January — she was in jail for “allegedly” stabbing someone.

Expat pressed on with her scheduled release, further motivated to expedite the royalty checks to bolster her commissary, if not her legal funds. What else could they do, besides casually utilizing her incarceration to hype the release, promising a handwritten letter from LA County Jail with every book sold? The first pressing sold out within a couple weeks.

Yet, it wasn’t just jailbird sensationalism that made Eris an Expat bestseller. She’s a notorious no-filter legend among the expanding “cyberwriter” community, her psycho-sexual drug-addled transmissions dropping on sites like surfaces and Terror House while often blurring into her real-time Twitter meltdowns.

The term cyberwriter is an in-joke among this post-alt-lit crowd, coined by Southern eccentric Jake Blackwood while Eris was in jail, the distinction quickly establishing itself into their collective lexicon. “What the fuck is cyberwriting?” she asked upon her release. “It’s YOU, Eris,” was the unanimous response. She represents a misunderstood generation of writers who spent copious time on public forums like livejournal, deadjournal, bleeding confessional diary pieces, trading voyeur/exhibitionist roles, unbeknownst they were establishing their chops by compulsively oversharing. Now, cyberwriters have a world of proper online sites to submit to, yet they accept their work’s terminal fate — read one day, forgotten the next. But that hopeless immediacy is the thrill of cyberwriting — you can almost hear the writer’s heavy breathing accompanying their words, as if they were ramping up to their last fatal scream into the void.

In his press release for Ruthless Little Things, Marrero recalls his encounter with Eris: “Glamorous, painful, fearlessly honest… when I met her, she was ready to die and I believed her.”

A month after her release from jail, I sat down with Eris to hear her side.

“Is there anything you don’t want me to bring up?” I asked her.

“Just try to make me uncomfortable. I dare you,” she said.

“I had just found out my girlfriend of seven years — who I met doing porn — died, so I was on the verge of suicide when I met Manuel. I was mourning but horny, writing a lot on social media. He thought my online expression was stellar and asked if I wrote outside of Twitter,” she said. “So, I compiled all my shit, just gave it to him in a big file, totally unprofessionally giving him some of it by .txt file. That all became Ruthless Little Things. I also gave him so many dark nights of the soul, he was really there when I needed him. And people talk about predatory editors — fuck that. I don’t even know what ‘grooming’ is. When I was thirteen, I was scamming people on Stickam. William Bernardara Jr. called me the ‘sexual predator’ of alt-lit. I was so flattered. But I’m just here, trying to make a difference in the world,” she says with a humbled giggle.

Eris is also a compelling voice, if not blunt critic, for those like her who struggle with Borderline Personality Disorder. “BPD is awful,” she says. “You just have to own it and accept it. Especially if you’re not gonna work on yourself and get better. Everyone talks about their crazy BPD ex, so it’s not like I have to be the first one to bring it up. I have a lot of crazy BPD ex-girlfriend stories and I’ve obviously been that girlfriend too.”

What makes Ruthless Little Things stand out from all the other Go Ask Alice type-cautionary tales of at-risk youth? It accounts for every imperfection and dangerous impulse without succumbing to the ubiquitous and pandering redemption arc. The result is an exhilarating joyride through the eyes of a peepshow girl, driven with insatiable lust to feel good by any means necessary, even if it kills her. The reader is gifted the vicarious pleasures of her blurred, kaleidoscopic catharsis, the howling yet introspective suicide missions lived out by Eris as your seedy urban safari guide, so we don’t have to disappoint our own parents firsthand. It’s a rare glimpse into modern no-tomorrow hedonism. She’s an endangered species in high heels stomping the glittery streets seeking to preserve misspent youth in whatever euphoric elixirs of immortality come her way. Because sometimes that’s all we need to get from one page to the next.

But in real life, what kind of fate awaits Eris, now that she’s facing possible prison time? Her release from jail last January merely proved a taunting intermission for these stabbing charges, which she describes as an unfortunate result of fight or flight instinct. It’s a complicated case for a complex girl, who somehow finds the strength to stay gallantly — and yes, defiantly — cheerful through it all.

“I think she feels consigned to a fate she can’t abide. But she’s the real thing, lives life on the edge of instinct and intuition, even if she’s now living on borrowed time,” says Marrero. “There’s no other era where her and I could have discovered one another. I’m glad the global village has welcomed her as the serious writer she is.”

But words don’t wait. Last May, Expat released the neo-pulp existential horror collection Bonding by Maggie Siebert. It’s urban Lovecraft, only tighter, less verbose; so the dread never overstays its welcome in the heart of our present-day malaise. It forces catharsis to our modern panic through unnamable nightmarish visuals that defy physics or logic, because these ugly, suffocated feelings we harbor must go out of our minds to be fully realized. With these quick bursts of anxiety and climax tailormade for the disinformation age, Siebert turns literary horror to high art, offering enduring parables for culture’s inexplicable lust to hit brick walls. Even potential theater is conjured in “Ammon” and “Marriage,” where she explores a strict dialogue format – you can hear these particular pieces scream to be performed as one act plays, triggering voices in our heads, a private Greek chorus.

But what is tragedy without comedy? I was howling through the pages of Family Annihilator by Calvin Westra, Expat’s latest release from July. A sharp, clever, meta-Turducken of a tale, a TV show within a book within a couple’s third mind that must break every wall to display its hidden tenderness. You could call it a wild card, an Expat curveball – but really, isn’t it all?

Meanwhile, Marrero has ushered in another cruel summer by hosting a series of full-capacity readings at an undisclosed rooftop in East Village. “It’s been a who’s who, over a hundred in attendance. Many have traveled over state lines for them. E-celebrities have shown up. The readings feel powerful and momentous,” says Marrero, offering a clear visual to these new huddled masses elevated against the New York skyline, one that seems comforting to view as a horizon with no limits.

PART 2: Self-immolation

The article you just read was actually rejected from the Prevailing L.A. Literary Site it was written for.

It may sound haughty, but I see journalism as a viable way to engineer culture; to help steer it in the direction I want to see it go, even if just getting it out of the garage in some cases. Selfishly, I often scan my periphery for what I’m about to deem “important” simply by the way its ripples resonate with me – and I prefer to highlight those who aren’t getting the immediate credit they deserve.

Shortly after I became an overnight fan of Expat Press last year, I immediately submitted some of my more hot-potato short fiction to Manuel Marrero. I began getting published regularly on the site, before becoming entrenched deeper into their orbit of authors because 1.) either I don’t know boundaries or 2.) they occupy a space in indie lit I always hoped could someday exist – heavy on style, vision, erraticism, and punk ethos – so naturally, I was rejoicing in their fierce output and felt a genuine camaraderie. Because of this, I’d be the first to admit my reporting wasn’t objective, but compulsive.

No one asked me, but I felt impulse to do something beyond the Lit Reactor interview I did with Manny in December 2020; to sort of give back, to shine an even brighter light on them. Despite their fanatical following, I saw an opportunity to break their story to a larger media outlet, where they might reach an even wider audience beyond the vast cult they had organically accrued. Since their L.A. author Elizabeth V. Aldrich AKA “Eris” had just missed the release of her debut novel Ruthless Little Things due to her incarceration, I saw the story as one with an even wider perspective of genuine pathos – perhaps an opportunity to give a voice to a drug addict with BPD, hopefully to smooth the bad influence Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl had on our culture’s compulsion to demonize BPD instead of understanding the millions who struggle with the condition. One could even argue our same broken culture that gives birth to the Borderline helps perpetuate it (I strongly suggest reading I Hate You – Don’t Leave Me by Jerold J. Kreisman, MD, and Hal Straus – an insightful no-stone-unturned clinical treatise on understanding Borderline Personality Disorder).

So, I was thrilled when my editor at The Prevailing L.A. Literary Site took the pitch – he agreed it would make for a compelling piece. A month later, I turned in the sprawling bullhorn expose on the breakout “transgressive” publisher and their female author who was now facing prison time for last year’s stabbing incident. In the piece, I present Expat as so aesthetically revolutionary, so literary daring that their books “contain enough inflammatory material to burn an art gallery down.”

Ironically, my article also contained enough inflammatory material to self-immolate in an unfortunate, but understandable zero-hour editorial critique and mass-redaction, reducing it to ashes.

“I’m so sorry to say this, but I’m afraid I can’t run this article,” my editor said. “I feel it’s exciting and important, shining a light on an emerging literary scene that deserves greater recognition, but as much as I hate the term ‘triggering,’ it will be so for a great many of our readers.”

He made it clear he would prefer seeing it in its original form elsewhere rather than him neuter the piece. Clearly, his hands were tied – despite his senior editor position, the ripple effect could have undermined trust in his leadership. My brain quaked, split hemispheres – one side taking this all on the chin, since I plan to be in this game for the long haul; the other half crushed, angry – not at my editor, but the state of our ever-tightening reactionary culture he must adhere to.

Remembering an editor’s responsibilities reach far beyond their red pen, I managed to stave off any delusions of censorship by calmly revisiting Arthur Plotnik’s essential Elements of Editing, Chapter 5: “Troubleshooting,” by lawyer Robert G. Sugarman:

“The one editorial skill that even the most Philistine media executives can appreciate is the ability to sniff out trouble before it gets into print…They learn how trouble can spring from minute or prodigious causes: a single careless word or a fundamental misunderstanding.”

In other words, it was the right time, but wrong place for the piece. I could foresee the alternate universe where it ran, where my talented (and actually, very tolerant) editor’s day or even week would get mired in angry emails, phone calls even staff distancing themselves from the organization. At that higher tier of media, it’s the senior editor’s duty to keep things moving, remaining on the path of least resistance. You could even say our culture’s reactionary tendencies are just as adversarial to a transgressive writer as it is to a senior editor – both prefer their instinctual tasks don’t become a Sisyphean chore.

It may seem regressive to present an article with its own sub-commentary introduction, but fair warning: you may see this often at The Last Estate, considering we specifically started this site as a place for creative reporting and cultural critique – although little would I know my redacted Expat piece might have a wider conversation because of its elimination. It’s further testimony to many points I make within the article – and like all the greatest art, Expat continues to possess a singular energy liable to repel as much as it attracts. And Hell, this piece is already its own time-capsule of sorts partly because of that dynamism – their masthead and authorship shifted last summer, stemming from a rather dramatic mutiny – but this seems part of Expat’s continued intent: to simply, though acutely, document moments in time.

They’re a publisher often known for blurring the lines of their own auto/meta-fiction, and before I knew it, I was pulled in the strange tides of my own documentation, when Marrero invited me to read at one of their infamous NYC rooftop events like the one I described right where I left off of my original piece.

So, I kept writing the article.

PART 3: Introduction to Vyvanse

Expat’s “Blank Swan” event, scheduled for November 13th, was to be their last of the year. Marrero expressed how exhausted he was after the late summer/fall turbulence climaxed at Angelfest (which they co-sponsored) when the event was infiltrated by NYC Antifa. “I have no idea, I guess Antifa just hates poetry or something? They looked like they wanted to kill us,” he said, after I asked what they could have possibly wanted from Expat.

“Reality and the internet got very close at Angelfest. They were making out, breathing down each other’s throats, touching midrifts – hot!” tweeted Scott Litts, Expat’s resident “ethicist.”

Further attraction to cultural extremes came earlier in September, when, for a couple weeks, notorious IG influencer Caroline Calloway became Expat’s most outspoken follower. “There goes your neighborhood,” I told him laughing, gnashing my teeth, after he had to explain to me who she was. Ever challenging the concept of “outsider,” Marrero agreed to have her read at an event, only to witness her use the gathering for her own shit-stirring callout confrontation to an audience member. One could debate her literary merit (to be fair, she has written a memoir), another could argue it was performance art; but these Expat readings attract a legitimate outlaw element that can test even the most refined spectator’s expectations.

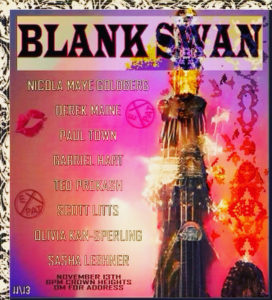

But despite Marrero’s commitment to situationist art, he seemed a bit overwhelmed by the boiling-over of the last two readings, these events perhaps becoming too inclusive for their own good. As a result, this upcoming “Blank Swan” was to be a tighter-knit affair at the rooftop of an undisclosed location to rekindle the original feel of the early gatherings. He kindly invited me to be a featured reader, alongside an eclectic yet perhaps less-combustible group comprised of Expat mainstay Ted Prokash (Wisconsin), Derek Maine (North Carolina), incel-satirist Paul Town, crime-writer Nicola Maye Goldberg, poet Sasha Leshner, Paris Review-writer Olivia Kan- Sperling, and Scott Litts, who tweeted that Hunter Biden was also attending the event.

I almost talked myself out of it — suddenly leaving my desert bubble seemed terrifying, I’ve been here alone for so long. But there’s a bubbling magnetism with a louder voice, telling me I’d be an idiot not to finally meet all these people I’ve been living with online and in their books for the past year. I’ve even become close friends with Elizabeth Aldrich since the original article. As I’m packing for the trip, she texts me a photo — not a nude like she’s often known for — but a fully-clothed snapshot of her folding herself up to demonstrate she could maybe fit in my luggage. “My ex used to call me Origami Girl,” she says. I’m totally impressed at the sight, while taken aback, as usual, by her ability to make herself appear so small. Throwing her into the mix of what might to be a boy’s club at Manuel’s apartment seems progressive, but her unfolding legal woes are confusing, convoluted enough that I fear I’d be harboring a fugitive over state lines.

Anxiety mounts when I arrive at the Palm Springs Airport, my first time flying since 2019. Ignorant to the latest pandemic protocols, it feels like my first time in the air, a kid again. But a child wouldn’t find his self in the airport’s bar, drinking my breakfast: two greyhounds (vitamin C) and one 16 oz. strong ale I am guzzling so quickly it’s dripping down my chin, when I see my plane is boarding around the corner. I find my seat, F20, and pull out my copy of CHAOS: Manson, The CIA, and the Secret History of the 60s; a book I somehow can’t put down despite the nightmares and waking stints of paranoid constellations it’s given me; the way it’s exploding my imagination into believing everything is connected, how nothing I was ever taught without experiencing first-hand isn’t even real. Maybe that’s why I’m going to New York, to prove to myself that I need to really, really meet these people in real life, or else it really is just another vague conspiracy I very well could be fooling myself about.

I look down at the desolate sepia floor of the Coachella Valley merging with the Sonora and the Mojave, borderless, fused by all the same dirt and sand, and I wonder where all those dirt roads lead. I wonder what’s really going on in those single warehouses miles away from anything, where there are no roads.

During my layover in Chicago, I get a message from Curtis Eggleston, thanking me for my review of his new Expat novel Hollow Nacelle in my recent Bear Creek Column. “I hope you cry tears of joy at altitude,” he says. “We will steer clear of stadiums,” I assure him.

From day to night, I arrive at La Guardia. It’s freezing, but after a twenty-minute cab ride I am greeted warmly by Marrero and his girlfriend Eva at his apartment in Ridgewood. Ted Prokash is already on his second night on Marrero’s couch. Prokash is more gentle and understated than how I imagined him from his rowdy online presence. He’s taking leisurely sips of the beer he’ll later call his “medicine,” speaking in slow, thoughtful, often humorous observations; yet he still casts a tuff Rust Belt shadow.

Marrero nearly introduces me as a journalist, then catches himself, “I don’t know, how do you see yourself, I don’t want to speak for you?” I want to elaborately quote John Hellman from Fables of Fact: The New Journalism’s New Fiction, where he argued New Journalism could be split into two camps: those who participate and those who observe. I would have then concluded by claiming the entrenched participant side of the coin if it hadn’t been a week later that I’d actually read that quote, so I settle for, “Whatever, I’m just a writer…”

After the four of us enjoy a contemplative view of the city on Marrero’s roof, a vibe of things to come since the weekend’s reading will be from a similar vantage, he shows me to my sleeping quarters. “You get to sleep in the library,” he says. Since I’m initially distracted by his voluminous shelves, it takes me a second to realize how much this is life imitating art, as I had just turned in my latest Bear Creek Gazette column, where I write from the perspective of a character who is camping out in the possessed town’s library. I don’t mention this, as I’d rather not distract from Marrero’s hospitality, not make it about myself, since he’s shown only genuine selflessness in the year I’ve known him.

I’d wait until I returned home to write this before I’d make it all about me.

We awake the next morning elated to hear that William Duryea, co-editor of Misery Tourism (and host of our online writing group Misery Loves Company), has made a last- minute decision to take the Greyhound up from Virginia for the reading. This adds a whole other level of urgency to the event: another co-sign of this summit’s compulsive magnetism, another vital head we get to meet in real life. He’ll be arriving at Port Authority right behind Derek Maine’s train into Grand Central Station.

Marrero mentioned Vyvanse; I asked him for one. I was once a teenage meth-head, then well-versed in gobbling my ex’s Adderall, yet I had yet to try this new elevated prescription drug that lately seemed to be on the tip of everyone’s tongue. “Speed, for the people,” he says, nodding with a Cubano James Dean smirk. This began a daily communion between him and I, washing our legal, clean productivity capsules down with our morning coffee before we would motormouth with the others. An hour later I am wholly impressed by this new wonder drug; one that actually – finally – makes me feel so comfortable in my own skin, I begin to wonder if I too, harbor some form of unchecked ADHD. Vyvanse reminds me the best drugs are the ones where 1.) no one can tell you’re on drugs and 2.) the drug actually integrates you into your environment rather than offering an escape. I’ve found the exodus aspect of drugs to be potentially alienating to others, the ones who have bravely chosen to actually engage their surroundings; while they inherit the responsibility of having to deal with you, the attempting escapee, who just can’t. And since I just got here, the last thing I want to do is escape New York.

Instead, we spend the day hitting pavement. I’m conquering record stores as efficient as a Japanese tourist, able to pull up/assess sixty-records every sixty seconds before I meet them at the bookstore. I’m there for fifteen minutes, and while I haven’t read every book in there, I am convinced I already know what every single one is about, the minutiae of their contents, by the time we leave.

We jam back to Marrero’s pad to meet Maine, then Duryea soon after. It’s a jubilant atmosphere, not at all weird as it could have been; there’s a feeling we’ve all smashed through the screen of social media and online journals to test our faith, our taste in fellowship. We all pass with flying colors, and not just because I’ve gotten a recent burst from my time released Vyvanse, an hourly reminder it’s still coursing thought my system. We can’t stop talking, though it’s still just Marrero and I mildly speeding along. Another test of our chemistry: three out of the five of us don’t even drink, so it feels all the more genuine no one needs that much grease to let down our guards. Writers familiar with each other’s work have this advantage — since we’ve already shown our vulnerabilities through our work, it’s as though we’ve all seen each other naked; a pre-leveled playing field.

Since our group has grown, and growing men must eat, we return to the streets, now the nightlife. Marrero takes us to Gordo’s Cantina, where we meet Misery Loves Company regular/longtime Brooklyn resident Michael McSweeney, who immediately feels like a window to the neighborhood’s history. Back at Marrero’s we all cram on the couch to commence a volleying tutorial on avant garde cinema. Remember: pretentiousness means you’ve simply given something a lot of thought. When it’s my turn, I turn them onto Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures. All eyes transfixed, I’m glad to be useful. We are pontificating, waxing heretics yet laughing like teenagers at a slumber party where no one wants to go to bed. But yet another thing I loved about Vyvanse: it allows me to.

#

I allow myself to sleep until 10am. In my super cute cactus pajamas, I enter the living room to a bustling scene. I’m late, everyone’s chopping it up without me. However, Marrero has just run the day’s feature on the Expat site, so I am right in time for our communion, our time-released rhythm continuum. I panic, realizing I haven’t taken a single photo. This scene needs instant documentation, a portrait of each player, solitaire on the couch, flush against the room’s brick wall. When it’s time for Marrero’s close-up, I insist he follows my direction for his own good:

“Okay, Manny, now let’s see a big confident smile… but not too confident! Let’s make it a nice, accessible smile — ‘cause we are re-branding you here, so you can subliminally atone for a transgressive publisher’s transgressions, to make yourself, you know, more appealing to all those who threw you under the subway train last summer, those writers who I’m not sure even write anymore — those who appear to be utilizing selfies as their main creative outlet. Wait, should we just make this look like a selfie? No? Okay. Good? That’s it. Perfect!”

Marrero has his own thoughts, thinking ahead to the evening. He proposes the “crazy idea” that Duryea hosts the reading instead of himself. It’s not a case of Marrero avoiding responsibility, more an acknowledgement of this natural host’s rare presence in the city. Duryea panics, then agrees, exhilarated. Maine and I are particularly enthused — since Duryea cancelled Misery Loves Company this week on account of traveling, we get to scratch that itch. Duryea has an impeccable knack for facilitating, assessing personalities, then commenting on a writer’s recitals.

The reading is on the roof of Scott Litts’s apartment in Crown Heights, where we arrive in our full pack. “Here are… my angels,” says Marrero, his smirk announcing our arrival to Scott and his roommates; it’s a self-effacing quip, no doubt poking fun at his impresario shadow he never asked for. It’s comfortably chaotic — Litts makes five different trips to the liquor store within a half hour as we wander around the living room, picking things up, putting them back down again, cups to lips, the heavy lifting getting lighter with every sip. The apartment becomes packed with heads, bodies, overdressed for the depleting oxygen inside. I see Joshua Chaplinsky, my editor at Lit Reactor, has arrived; then my wide-eyed friend Ammo from Los Angeles, who has escaped that particular Babylon, into another. Soon, at least sixty people in one room, sweating profusely. I perceive Marrero in panic, so without thinking, I appoint myself to cup my hands and yell, “Everyone to the roof.” I hear the propelling sound of 120 soles stomping up the stairs behind me, too late to turn back now.

It’s immediately ceremonial, everyone knows where to go. The spectators, who are also participants, make a horseshoe formation, sacrificing their backsides, offering a wall from the frigid wind. Us readers, one by one, step up behind a solitary blue light that gives a warmth of focus; allowing our voices to shiver freely. There’s a rawness here, don’t blink or you’ll miss it.

Duryea takes the mic, introducing himself as co-editor of the “third most cancelled literary journal on the internet” before presenting Sasha Leshner, our sacrificial lamb, a young woman who immediately appears like living, breathing poetry. I’m instantly drawn to her — she resembles a female Rowland S. Howard; sleek, bundled beneath a dark coat like 3-D silhouette, a woman out of time. Her presence inspires instant quiet to the tooth-chattering captives. Her verses drip, cascade; depression as a warm blanket, apocalypse as an end to worry. I love the way she utters “oleander.” All were still, breathless while she spoke, her warnings and real-time premonitions folding in on themselves. While Leshner finished, a freezing wind began, like she brought it herself, one last statement.

Duryea introduces Olivia Kan-Sperling as the writer who just got Expat into the Paris Review — Marrero runs up, whispers in Duryea’s ear, a slight faux pas of incomplete generalization. Sperling ends up speaking for herself by just reading; strong, sincere first-person fiction proving her range beyond journalist.

Next is Litts, the first to shatter any assumptions the night could take itself too seriously. We can smell the garlic singe our nose-hairs, feel the acid-reflux burn our throats in his observational subway piece, “A Meaningless Exercise in Self Discipline,” (published online by Back Patio Press, 2019). I’m doubling over, bellowing a cackle that shamefully cuts through everyone else’s polite giggling before I can restrain myself.

Ted Prokash follows, underdressed in a thin grey hoodie cinched all the way over his face, tied at his nose. As a fan of Prokash, I’ve been dying to know what he’s going to read. We’re treated to a meaty excerpt from his novel in progress BOINGERS! A Club for Gentlemen; a boozy, bawdy, post-modern post-nautical romp for land-lovers. Delivered in his native Wisconsinese, he throws bar after bar, triggering the heartiest of hardy-har-hars amongst the trembling throng. Prokash possesses one of the widest ranges out of any current author I’m aware of, an acute grasp and wield of language. I finally read Moby Dick earlier this year over a three-month slog, and after hearing this piece of BOINGERS tonight, I feel wistful that Melville’s failed novel could have benefitted from a sharper captain like Prokash steering the ship.

I brought a stack of my newest book to NYC with me, a noir/speculative-fiction collection published by Close to the Bone, my U.K. publisher. Why I mention this: I forgot the books at Marrero’s apartment. I briefly scold myself, lamenting the books travelling all this way with me, taking up valuable real-estate in my luggage, only to fail selling them at the reading — you know, be a real, working author. I quickly realize it’s a resolute problem to have — I was having too good of a time to concern myself with turning art into commerce. It’s not really that kind of reading, anyway. Marrero prefers to call these shows, not readings; more akin to the unpredictability of DIY punk than a dubiously regimented bookstore gathering. The imperative is presence, a moment in time, creating a memory that cannot be a facsimile, a psychic NFT for our minds only.

Regardless, it’s my turn. Duryea introduces me to the crowd as his friend, and at that moment there’s no other way I want to be described; it sounds better than a journalist or even a writer, really. I choose to read my recent Expat piece “Pitchfork After Scythe” because reading it on a freezing rooftop on the other side of the country in front of fifty strangers feels like the safest way to share something so personal; though I maintain its fiction — memory as the unreliable narrator.

Derek Maine goes after me, thank God. This ain’t a contest but it’s always tough to follow him at Misery Loves Company. A reading from Maine is much more than that; it’s a performance, no beat missed. His urgent cadence like a runaway, determined train; or maybe its anxiety-ridden Southern conductor, describing to us gasping passengers all the obstacles barricading our tracks. Tonight, he reads “The Dolphin Lane Motel (Off-Season 1993-1996),” originally published in the 2020 winter issue of Ligeia Magazine, on this rooftop where he has all the room to pace.

Recently, in the spirit of keeping everyone guessing, Expat has embraced the gnarlier bracket of the noir contingent, so when crime-writer Nicola Maye Goldberg was asked to read for the event, it only made sense. She opens with a sarcastic quip, “So, I heard you all like autofiction? Well, I got something here for you…” Oddly, her offering was not autofiction, but a tight epistolary piece — a sympathetic open letter to notorious serial killer Aileen Wuornos, giving true-crime a feminist bend. “Men like to tell us to get back in the kitchen as if that’s not where we keep our knives, they love to put their cocks in our mouths, like that’s not where we keep our teeth…” Killer.

Headliner Paul Town’s reputation preceded his appearance. To his detractors, Town might be perceived as an outspoken, controversial incel king. Marrero, however, sees him a writer with a unique voice, and genuinely felt an Expat reading might be the only place to give him a serious platform to be re-evaluated by literature people. Town reads from his infamous self-published thicky It Is the Secret, a sprawling tome of cruel philosophical vignettes of overcompensating masculinity that I couldn’t put down at Marrero’s apartment. His hybrid tone meets at the unlikely intersection of Crispin Glover and Jim Goad. Since no one here is an idiot, most are dying of laughter when he reads — surrendering to the rush, the precarious dangle of not knowing – and not caring – whether it’s a joke or not. Twitter, however, didn’t join in our revelry with Town, when they banned him from the site just a couple days after the reading.

The following day, a Sunday, we saw off Maine, Duryea, and Prokash in staggered exits, leaving Marrero and I to salvage the last hours of my final day. “Do you play chess?” he asks. I’ve always wanted to learn; I decide now is the time. We post up at the Bad Old Days, a dark, quiet drinking hole around the corner whose built-in chessboard has green and white squares. Marrero teaches me the rules as we play, allowing me to make mistakes first before he suggests better strategies. I feel like I’ve accomplished something important by acquiring this new armchair athleticism, even while my mind is struggling to retain the rules of the game; and because Marrero is planting these seeds, he’s able to get further under my skin without even trying; so much so, that it’s not until my long plane ride home that I finally wonder what his next move will be.