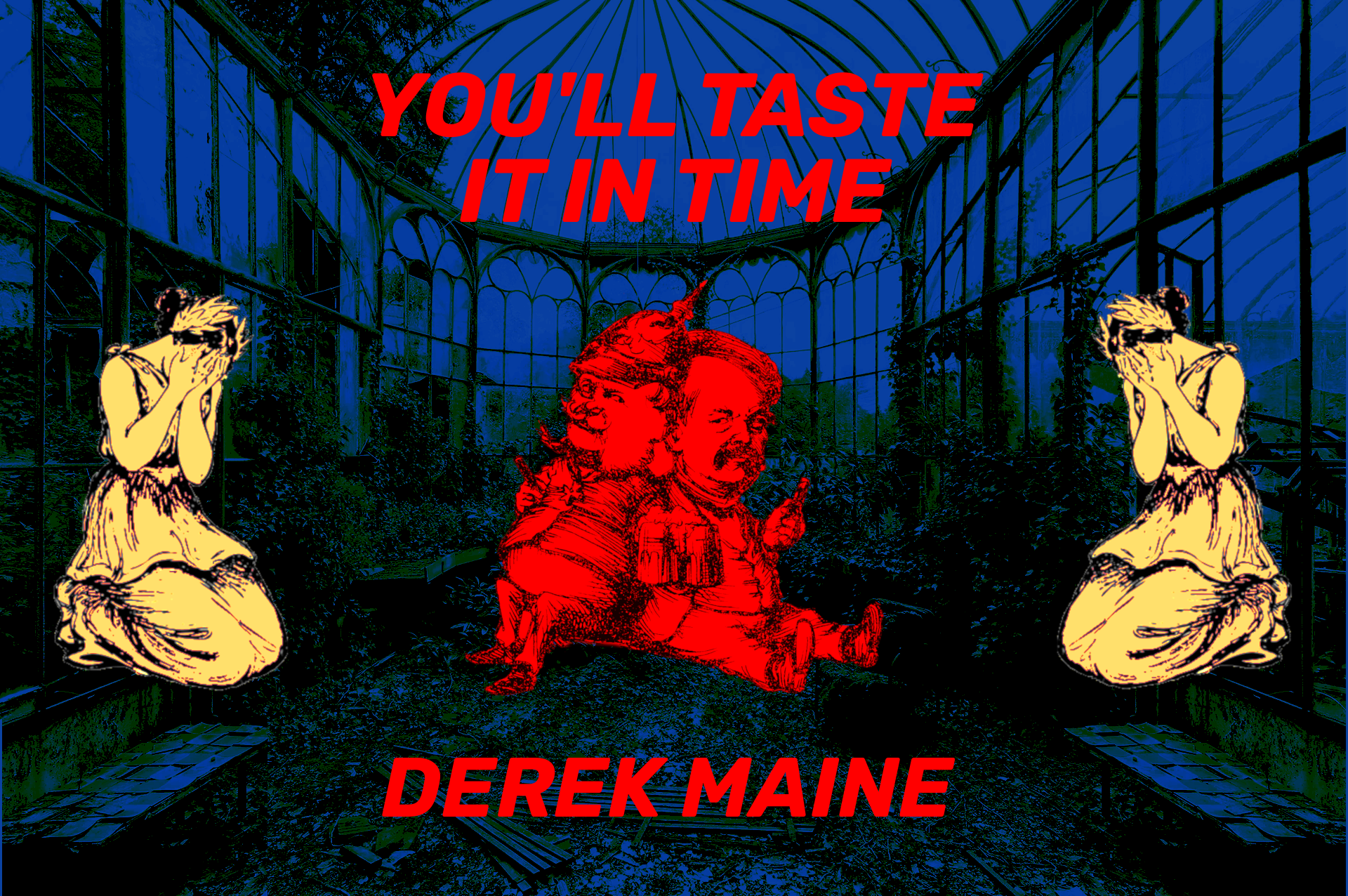

“YOU’LL TASTE IT IN TIME”

On Graham Irvin’s Liver Mush (Back Patio Press, 2022)

I do not know how to read poetry I am always alone up here in this consciousness container The truth is I seek a temporary reprieve without the drama and permanence of canceling my own existence plus I have children to care for A wife to love I want to know what it is like where you are in the world Is it rain Is it cold Are there trees

What can we express in language that can be expressed no other way? The voices in your head speaking to the voices in my head, mixing and mingling memory with meaning in service of a private literature. This dance between reader and writer is my own temporary reprieve. The distance between your thought and mine cannot be measured in time or coffee spoons: the poet seeks an eternal present, to preserve these moments in amber. It is rare and it is beautiful and it is not unlike magic, turning to a page or a phrase to renew a conversation.

Graham Irvin, a poet from North Carolina, residing in Philadelphia, working in a warehouse in New Jersey. Graham Irvin invites us to taste it, to take Liver Mush from our table to our tongue and touch God.

“I want liver mush to mean as much as possible,

to as many people as possible” (from ‘Let’s Start Over’, pg. 24)

The repetition, in Liver Mush, like an Epizeuxis hammer, anaphoric wind tunnel of screams, epimone moan, antanaclasis master class of meaning, until it settles in our throat, favorably flavored with sage from a sage, assuaging us, dear readers, from having to venture into that forest of feelings alone. Everywhere there are guides, and signposts, and shamans. We are traveling trails trodden by all those come before us, similarly swept up by the power and glory of language, forever and ever amen.

My belly is full. My belly is warm. My belly hurts. From having eaten too much or too little. From eating the wrong things. This is not one of those things. Liver Mush, the collection of 48 poems + 1 recipe, or 48 recipes + 1 poem, is the stuff of real, sustained nourishment. It’s the whole hog, as we say down here.

“Liver mush is just a word, but the word means nothing to almost everyone and to me it’s cracking open my skull, puréeing my memories into a grey mush, and shaping them into something that looks familiar to anyone reading this.” (from ‘Liver Mush is An Essay About My Mom,’ pg. 43)

In Liver Mush, in Graham Irvin’s memories, there are dead fathers, pious, worrying mothers, an unchanging and unknowable south, love, t-shirts to cure depression, spices, more sage, the monotony and pain of just living regular, memories retold as mush or memories disguised as mush or all of it only ever and just mush, including your memories and mine.

In my mouth Liver Mush, the pork product, is too greasy. Mouth feels like slime. Fat from the gristle sticky on my tongue. In Graham Irvin’s mouth it is something else entirely. Taste as an explosion of memory on place, loss, and love. The sadness in things coming to pass and then, ultimately, passing on. Some meals in between. Do they serve deviled eggs at funerals where you are? Moravian Chicken Pot Pie at Church bake sales? Do some things linger longer than others? Is it palpable? Can you taste it? You will, in time.

“This is in service of tasting my memories.

This is in service of you becoming the closest version of me you can get.” (from ‘Vegan Liver Mush Recipe,’ page 101)

You can follow Graham Irvin’s recipe for Vegan Liver Mush or you can go to the store, down here where I’m from, and get yourself a block of the stuff.

I need to bite into something that used to be alive. I do need to feel my suffering was not unique. Graham Irvin lets us taste it. He does, with words, what I wanted all along: to stare into this abyss with someone else, to taste it as they tasted it. The defining feature of our connected world is our unceasing, unflinching, irredeemable loneliness within it, and while I sat on gym floors watching my children play, I felt less alone, for several hours, a few times a week, in a brutally cold January, Southeastern United States and all that brings to bear, tasting Graham Irvin’s memories, reading and re-rereading Liver Mush (Back Patio, 2022), during basketball practices, stomach rumbling.